Anti-racism movements are in no way new. They often come in waves, from the American civil war to the decolonisation of commonwealth countries; today it is the Black Lives Matter protests. These protests led to national, and even international, controversies [1, 2], whilst often times also being successful in their aim [3, 4, 5]. Although racism is often brought up in our society, especially under the current climate, its relation to health is often left undiscussed [6]. To open a dialogue about today’s relationship between race and health cannot take place until we break down that of yesterday’s.

A gruesome history

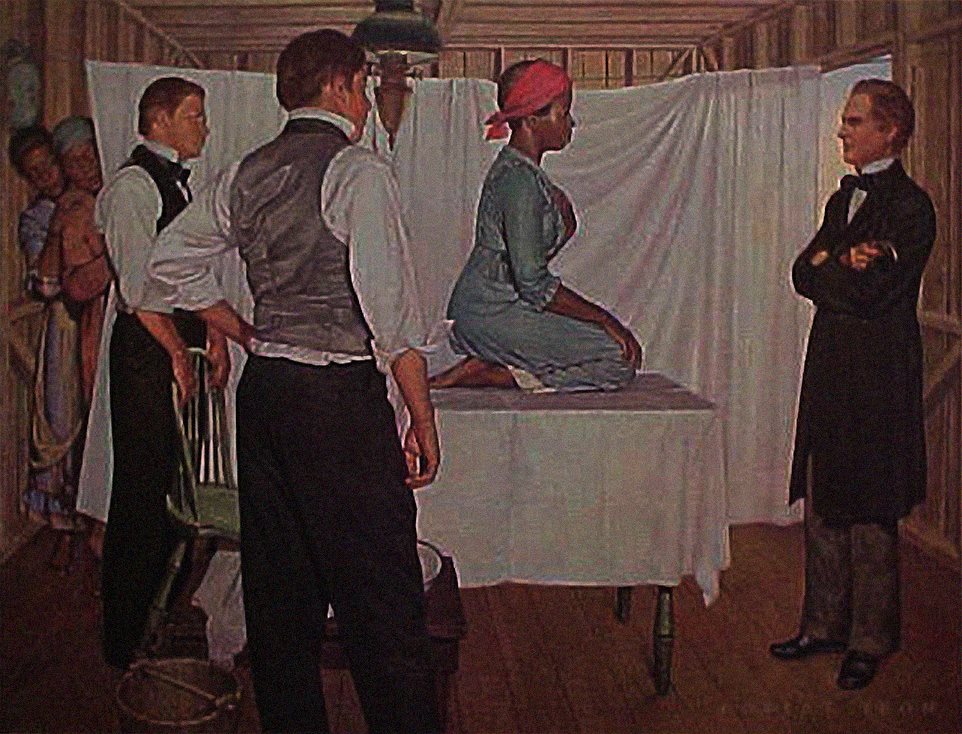

For a long time, racism has been at the foundations of medical history. The Tuskegee Syphilis experiment might be the most infamous but it is far from the only experiment profiting from racism. One of the many similarly themed legacies is the case of James Marion Sims, well known as the father of modern gynaecology. A legacy built on the research conducted on 3 slaves, Anarcha, Betsey and Lucy. He practiced and researched his new developments in gynaecological surgery on each of his victims up to 30 times each over 4 years, without anaesthetics [7]. Not only was he a well-respected gynaecologist for his time (and debatably ours), he went on to become the president of the American Medical Association in 1876 [8]. What may surprise us today is that his research was well justified by many, because the consensus of that time considered people of colour to have smaller brains as well as being ‘more insensible to pain’ than their counterparts [8]. Of course, this was a means to justify the brutal torture of slaves in plantations which later went onto also justify the excruciating torture of Sims’ victims [8]. A similar case of racial injustice within this field includes the unconsented use of HeLa cells for research with aims of profit [9].

Medical research such as these were not the only form of racism prevalent in medicine however. Medical education played a vital role in the public’s acceptance of slavery. In the late 1790s, the theory of Polygenesis was popularised. This theory suggested that God created each human race separately and consequently that these were created to live in their, so-called, native climates [10]. This premise, be it false, was often used to argue for the belief that the black community thrives when working on plantations. Professor Benjamin Rush, a founding father of the University of Pennsylvania, would often teach his students that ‘blackness was a form of leprosy’, which would one day be cured [10].

When taking all of this into consideration, it is vital not to assume that these issues are exclusive to the United States, when the role of the United Kingdom in medical racism was far from little. William Wright was a medical doctor qualified from University of St Andrews and attended lectures from the University of Edinburgh. Within 6 months of setting up his clinic, he owned 4 slaves. This quickly expanded, and by 1771 he owned as many as 33 slaves [11]. Furthermore, it is important to recognise that the treatment of slaves was not intended as a kindness but indisputably for economic benefit. This can be seen by a quote of Wright, in a letter he wrote to his brother in 1792, where he said that the end to slavery would be “fatal to our commerce, ruinous to our islands, destructive to our countrymen, and in no way serving the cause of humanity” [11].

This historical overview clearly shows that race has had a long, unhealthy relationship with healthcare, regardless of whether it be in the UK or elsewhere. The impacts of this were nothing short of disastrous and have undoubtedly influenced our society today. The only question is how.

References

[1] Kevin Liptak & Kristen Holmes. Trump calls Black Lives Matter a ‘symbol of hate’ as he digs in on race. CNN, Jul 1, 2020.

[2] Naman Ramachandran. Complaints Cross 21,000 for Black Lives Matter-Inspired ‘Britain’s Got Talent’ Routine, Judge Details Racist Abuse. Variety, Sep 14, 2020.

[3] Austa Somvichian-Clausen. What the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests have achieved so far. The Hill, Jun 10, 2020

[4] Katie O’Malley. How Black Lives Matter Protests Have Changed The World, A Month After George Floyd’s Death. ELLE, Jun 26, 2020.

[5] Nate Cohn & Kevin Quealy. How Public Opinion Has Moved on Black Lives Matter. The New York Times, Jun 10, 2020.

[6] Victor Adebowale. It’s time to act on racism in the NHS. BMJ, 2020;368:m568

[7] Sarah Lynch. Fact check: Father of modern gynecology performed experiments on enslaved Black women. USA Today, Jun 20, 2020

[8] Keith Wailoo. Historical Aspects of Race and Medicine: The Case of J. Marion Sims. JAMA, 2018;320(15):1529-1530.

[9] Rebecca Skloot. The Immortal Life Of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Crown Publishers, 2010. Print.

[10] Christopher Willoughby. Racist medicine: a history of race and health. OUPblog, Sep 12, 2017.

[11] Daisy Chamberlain. Edinburgh-trained doctors on Caribbean plantations. UNCOVERED, Aug 28, 2019.